the well driller

by Michael Templeton

I recall with all my lives

my reasons for forgetting.

--Alejandra Pizarnik

There are certain memories that belong to a realm unconnected to the more coherent ones that form the stories of my life. While I have many intense and detailed memories, enough for me to have written a memoir, I also have some that exist in a space of enigma, the space where memory and forgetting form a chemical suspension—the way certain oils and solids can be held in water without pulling apart. These are not stories. The French language has the term “récit,” a form one could associate most strongly with the work of Maurice Blanchot. Récits and fragments are forms ideal for conveying memories that do not completely emerge as narratives or stories. Lydia Davis’s translation of Blanchot’s The Madness of the Day ends: “A story? No. No stories, never again.” ‘Story’ appears to be the closest approximation to récit, but this does not really convey all that comes with the French term. Récit means something, both more and less; a récit, perhaps, can convey something that is situated in a suspension on the cusp of memory and forgetting. So, “Un récit? Non, pas récit, plus jamais.”

Un récit:

My memory of him always begins with him at the center and somehow both near and far. (The memory is lodged at the edge—the undeterminable—where forgetting and memory merge, before the mind becomes sutured to other meanings that give meaning to meaning and make forgetting impossible, and memory becomes the endless memory of memory). At the center and high up in a space of that bare rock near the lake. The sun was blinding as it beat down on the rock and was reflected back from the pale Kentucky sandstone. Smooth and marbled with shades of brown and beige and light red, and he atop it all in that strange machine that was so loud as it shot out smoke and splashes of gray muddy water—the gray a sign he had gotten below the sandstone toward the aquifer (how far down no one knew). At the center of the earth in my imagination. He and the machine, distant but clear, the sandstone spreading out in all directions, smooth but uneven, the sun beaming over everything and reflected back out by the sandstone, and the machine a foreign and bizarre apparition. The complex and intricate mechanics and the sound—loud, multiple sounds—of the engine and the pounding of the drilling rod into the earth.

And in the center of the broad rock, he was at the center of the great machine. Rods and rails, pipes and connections, the powerful engine at the center-bottom, and he at the center-rear, with the great drilling rod that slammed up and down into the rock; I could not fathom how far down. He seemed so calm, even as the machine jostled him every which way, as the great drill slammed up and down. The noise terrified me, but the man appeared completely unaffected. Oblivious, it seemed, to the vibrations and shocks, or to the splashes of gray muddy water that soaked him and immediately began to dry in the powerful sun, leaving great crusts of gray clay on his face, hands…his coveralls coated. And again, he seemed completely undaunted, unbothered. He was a part of that machine, and he was just as much a part of the deep earth below him as he drilled further and further to find the aquifer. And although everything in this moment made me afraid, curiosity took the greater part of my consciousness as the man seemed so at ease with that machine; the way a man is with a large animal only he knows how to control. All of it so foreign to me, having never in my life seen anything like it before or since.

My father approached the man and his machine, and I was just behind, although I have no memory of walking. We seem to have suddenly appeared next to them. The man became aware of us and began switching down the machine, bringing the great drilling rod to a stop and shutting down the engine. The noise stopped. The smoke floated off—gray blue smoke like the gray blue mud. He then pulled himself out of the machine and spoke with my father. I had no idea what they said. That foreign chatter of adults that did not include children, holding no interest for us. Murmurings of nothings. I held back with a mix of trepidation and curiosity like an animal seeing a human for the first time. Curious but feeling an innate fear connected to self-preservation. The man was that machine, and the machine was that man. But he smiled at us both, my father and I. Looking down at me smiling. He seemed to be genuinely happy to see us and to have this unexpected visit.

It was then that he reached behind the seat of the machine and pulled out a jar of clear water and a single ripe tomato that all seemed absolutely strange and unlikely to me. Why would he have water in an old jar, and why would he only have a single tomato for his food? I thought of coal miners or lumberjacks who in the storybooks ate big meals of flapjacks and beans and ham and cornbread. But this man…just a plain jar of clear water and a single tomato. The perfectly ripe summer tomato, perfectly clean amidst all that dirt. But the jar had splashes of the gray mud. And with a naturalness of something that was inevitable, that man offered me a drink and a bite. I was fascinated, terrified, sickened, and astonished—it seems impossible to explain. A confusion I have never felt at any other time in my life, so I refused. I backed way like a scared dog, saying nothing. The man and my father laughed at my timidness, but I was out of my depth in a foreign place with a man and a contraption I had no way of understanding. It all became a reality so immediate it faded into hallucination, and I—my complete sense of myself—just disappeared into a dissociation. That man, that machine that drilled into the earth to find nothing more profound than water, and the jar of water gleaming in the sun, illuminated from above and below with a bright blinding Kentucky sun on the bright and blinding Kentucky sandstone. That gleaming water in a simple jar splattered with gray mud, and that simple but perfect red ripe summer tomato. All of it collapsing into a condensed frozen isolate of inarticulable fear, sublimity, perfection, stillness, movement and livingness at the same time; my living, human self drifting away in the face of it all. More animal than child.

The way I have written this will never again come to me as I have written it. The récit emerged in this form only this one time. It has always been with me, though, all these years, lying within me with the weight of all the other things I have forgotten. The well driller can now return to the spaces of memory and forgetting, to the space of enigma. “Un récit? Non, pas récit, plus jamais.”

*********

What brings the events to memory? He does not indicate how or why the récit is brought up from that space of enigma. Something always happens that spurs an idea from deep within the mind that brings it forth. A smell, an aroma, a moment of recognition, a song or just a fragment of a melody—anything can do it, but something always precedes a recollection. It is the nature of memory and recollection that it proceed via association. Thus, the term “re-collection;” one collects again or anew because that which lies near or adjacent has made contact with something else which is near or adjacent. Here, the narrator does not tell us what brought this event to the forefront of his mind. The narrator refers to Blanchot, who does write about memory and forgetting.

Blanchot tells us that “(f)orgetting causes language to rise up in its entirety by gathering around the forgotten word” (The Infinite Conversation, 194). Like blood cells around an injury, the mind mobilizes language around the wound in consciousness that is the forgotten thing. The forgotten word forces us to mobilize all the words near and adjacent to the now empty space where the forgotten word or idea was once found. We are familiar with these moments in which we struggle to recall a specific word, and no matter how many words others may offer us, we cannot be satisfied until precisely the correct word is found. Nothing will stand in, even though other words may be perfectly acceptable substitutes with meanings nearly identical to the one that is lost (although we know the meanings of words, no matter how close they may be as synonyms, never mean precisely the same thing). When we find the forgotten word, we know, we just know because “when we are missing a word it still indicates itself through this lack; we have the word as something forgotten, and thus reaffirm it in the absence it seemed made to fill and whose place it seemed made to dissimulate” (194). The récit indicates this place, this emptiness as the narrator explains that the “well driller can now return to the spaces of memory and forgetting, to the space of enigma.” The absence of the thing is known; there is a presence to the absence in the place where it is meant to fill, and we know this by all the words and terms which surround this place. Whatever the narrator means by “the space of enigma,” we must surmise that it is the same absence which is rendered knowable at the moment the memory or the word comes forth and is then forgotten again. Perhaps this is what the narrator means when they explain that a récit offers both less and more; less, because the récit never indicates that it could be a part of a larger narrative that could fill in things, such as context, history, personal or political meaning, etc.; more, because the récit everywhere indicates that it is loaded with meanings, one of which is this very process of memory and forgetting.

There are a number of ways to translate the term ‘récit.’ Lydia Davis, the translator of Blanchot, offers “story” as a suitable translation, and the narrator above uses ‘récit’ because it is Blanchot’s term, and it has the feel of correctness. The problem of memory and forgetting and that of language and translation all contribute to a difficulty as to how to understand the text since the narrator explains that it is on the edge of memory and forgetting, and therefore may not ever have happened, but is nevertheless retrieved by the narrator from the space of forgetting wherein one searches the space of the absence left by what has been forgotten for the thing forgotten. The process of searching for that which is lost (to forgetting) is compounded by the process of searching for a correct term. Both of these are now entwined in a gordian knot of memory and forgetting and the problem of the proper as it pertains to narrative form.

By way of finding a point of purchase, the final paragraph, which is set off from the narrative proper (“narrative” is still another potential translation of the récit), the narrator tells us that the text, as it is written, “will never again come to me as I have written it. The récit emerged in this form only this one time.” The term to grasp is ‘emerge.’ The récit emerged as it is and will never emerge in this way again. The emergence of the text appears to have emerged with the form of the text. Form and content emerged as it is from out of the space of memory and forgetting. To this end, the nature of the text is important to the way we can understand the use of memory insofar as the form of the memory is the vessel within which the memory emerges from the space of memory and forgetting, and the memory emerges as it is brought into the light of remembering insofar as the vessel, the form, emerges from the space of memory and forgetting. Yet, given the information in the memory and in the introductory paragraph and the final paragraph, “(i)t is impossible to decide whether an event, account, account of event or event of accounting took place” (Derrida. “The Law of Genre,” 218). The confusion of our text is caught up in the nature of Derrida’s problematizing of the form of the text in which he tells us that the formal features of the text confuse the very questions of form. Specifically in this case, we are not sure if the form in which the text is given is a genre or a mode because as Derrida explains, there are genres, properly speaking, and “there are modes, for example the récit” (209). The form or mode emerges, we are to understand, as the content of the memory. The two things are of a piece as they are retrieved from memory, but, as we are told from the introductory paragraph, there are some memories which have greater consistency than others, and the memory that is to be recounted does not have this kind of consistency. Still more, the narrator explains that they have “many intense and detailed memories, enough for me to have written a memoir.” The narrator, then, is, by their own account, a teller of tales, one who has the ability and talents for telling stories, a storyteller, as it were. The narrator is one who presumably understands the conventions of telling stories, how to make them both plausible and interesting. Yet, this memory, the one which forms the bulk of the text, is a memory taken from “a space of enigma,” and the unfinished, inconsistent and less “intense and detailed” memory which forms this text is not of the same order as that of a clear memory. The form or mode of the récit, with its formal structures and features, is somehow less than that of a genre, according to Derrida, lends itself as a vehicle to recount and at least partially retrieve the indeterminate memory which we are then given in the body of the text. Everything becomes precarious.

It is not that anything I have said here should impugn the truth of the récit. The text does not tell us anything of any real import other than that it may be interesting to some. We lose or gain nothing by suggesting the text is true or untrue. And the facts of the text do not lead us anywhere dangerous or momentous. We would gain nothing by bringing a Freudian analysis, for example, other than a prurient understanding of the text. What is at issue is the problem of remembering and forgetting and the way the form of the memory brings forth the content and vice versa. Blanchot explains that when we forget a word, “we seize in the word forgotten the space out of which it speaks, and that now refers us back to its silent, unavailable, interdicted and still latent meaning” (The Infinite Conversation, 194). In our fury to remember what is forgotten, we grasp at emptiness from an empty space that is not only empty but also no longer available and is somehow “interdicted,” delimited by an official word or decree as off-limits. That which is forgotten is barred from memory by an inter-dict, a word between, a linguistic barrier to the linguistic artifact which makes up the substance/content, and in the case of our above récit, is retrieved from beyond the interdict via a specific linguistic shape or form which emerges simultaneously with the content.

In grasping for the substance of the memory which makes up the bulk of our text under discussion, the narrator has in some way withdrawn from this empty, absent, and foreclosed space the elements of something that functions on the order of a memory, one so filled with meaning that the colors and sounds, and even the visceral reactions to these colors and sounds, can be accessed at least long enough to assemble them in this particular form just this one and only time.

It may be that what is of primary importance is not the pathways through which the substance of the memory comes to adhere and fill out the form of the memory as a récit, but the voice which recounts all that is alleged to have occurred somewhere in a dim past unavailable to us the readers and only tenuously available to the narrative voice that tells the tale. The formal structure of the récit, which captures both less and more of the memory recounted above, is given through a narrative voice which speaks from “a certain neutrality... from which the ‘I’ posits and identifies itself” (Derrida. Demeure: Fiction and Testimony, 26). Although the narrator recounts from the position of the first person narrator, the memory is given through that placeless and person-less position occupies by the very absence which invokes the space of absence from which the form and content is then presented within the formal “mode’ said to be that of the récit—a formal mode which emerges with the content which fills out the form, the same formal mode which presents us with the “I” that speaks.

From the space of forgetting, which is barred by the linguistic mode of the interdict, a form of barrier in language, there is an absence. Out of this absence, the substance or presence of memory emerges in the form of a récit that is recounted above which will, it is stated, return to an ambiguous place of enigma. The form given, the récit, is the inevitable form insofar as it makes it possible to render into the formal presence of language, the content of that which emerges from the space of enigma. Thus, we have the image, in narrative form, of the absence in the space of forgetting as it comes to memory, and as the form of the memory emerges, simultaneously, and is then recounted via the empty space of a narrative voice which purports to be the “I” of the récit but is also the absence of the “I” who speaks or writes so that the récit given above is the only thing, in its material form as written words on a page, that can be said to have come into existence. The speaker/narrator, the space of forgetting, the space of enigma, and the formal mode by which all is contained then recede into an emptiness and absence. Nothing is left but the récit which is precisely why the récit is framed from the beginning and the end by the narrative directive that there will never again be stories or récits. “Un récit? Non, pas récit, plus jamais.” And this is a quotation from another récit which is said to never come again. In the final analysis, the récit and the “I” who speaks fall into the enigma itself, becoming “the ‘I’-less ‘I’ of the narrative voice, the ‘I’ stripped of itself, the one that does not take place” (224). My own memory and I, the one who remembers and the one who writes, are all the fragment shards of something that can recede back into the space of forgetting, back into the enigma, and I, the one who writes, can leave this to you, the one who reads, and nothing ever needs to be said about any of this ever again.

Works Cited:

Blanchot, Maurice. The Infinite Conversation. Tr. Susan Hanson. Theory and History of Literature. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

Blanchot, Maurice. Jacques Derrida. The Instant of My Death/ Demeure: Fiction and Testimony.

Tr. Elizabeth Rottenberg. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998.

The Madness of the Day. Tr. Lydia Davis. Barrytown: Station Hill Press, 1981.

Derrida, Jacques. Glyph: Textual Studies 7. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1980.

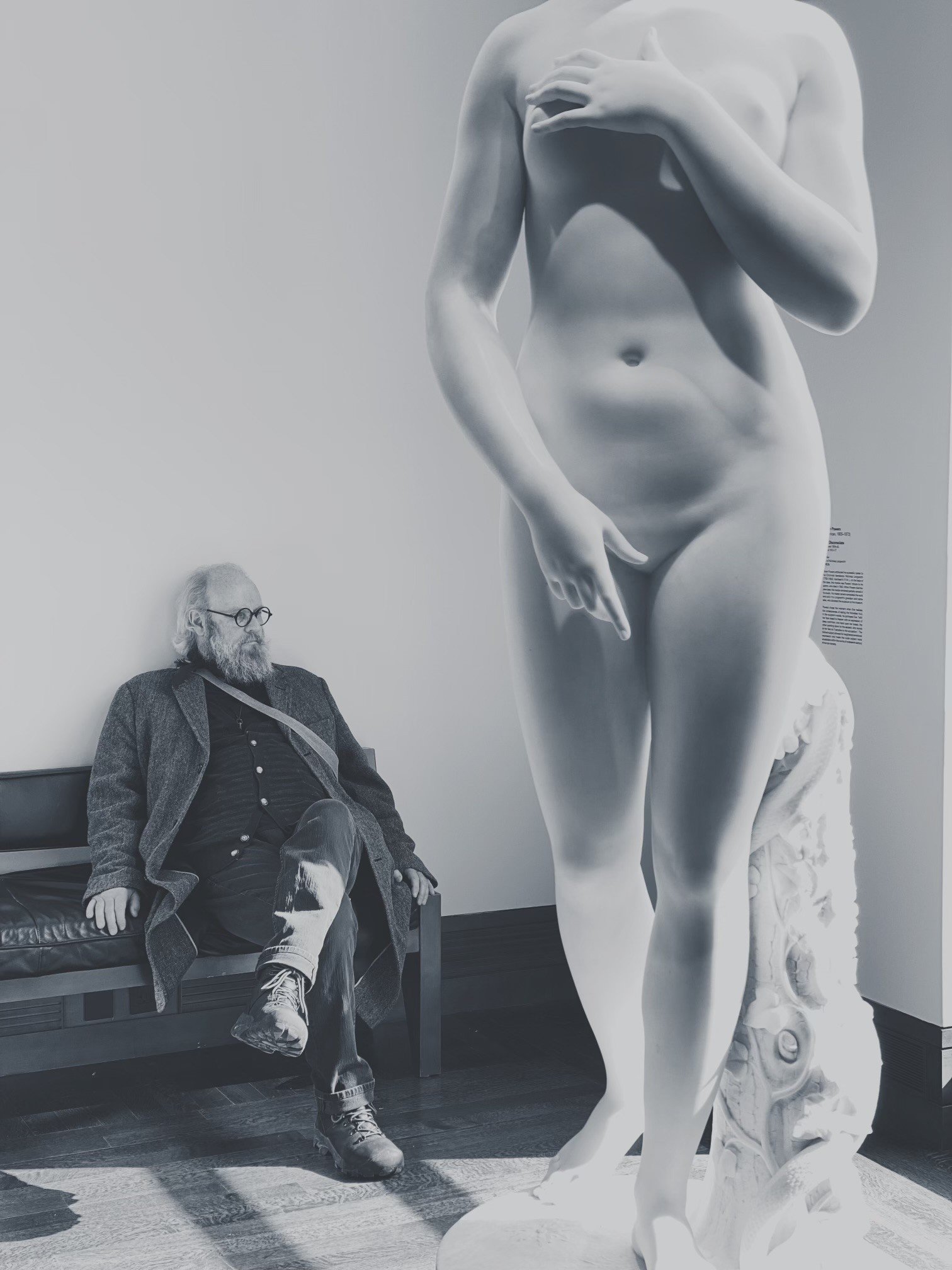

Photo of Michael Templeton

BIO: Michael Templeton is a writer and independent scholar. He is the author of The Chief of Birds: A Memoir published with Erratum Press, the awaiting of awaiting: a novella with Nut Hole Publishing, and Impossible to Believe, from Iff Books, and The Ohiomachine forthcoming with Punctum Books. He is also the author of Collected Apoems, forthcoming from LJMcD Communications He has published articles and essays on contemporary culture and numerous works of creative non-fiction as well as experimental works and poetry. He lives in the middle of nowhere in Ohio with his wife who is an artist.