the smallest way: a self-incriminating memoir

by Luke Carter

I don’t sleep much these days. It’s not caffeine or screens or guilt over something domestic. It’s the quiet kind of insomnia, the kind that begins when you realise your government funds murder and your neighbours help build the machinery. My girlfriend, ever-observant, cottoned on to my nocturnal preoccupations a long while ago: at first she feared the worst—guilt-induced insomnia from a well-hidden affair; nighttime scheming to break her heart—but she never predicted the real reason for my unsleeping.

We humans evolved in circumstances wildly different from those we now inhabit. Our bodies and minds were tuned for running, foraging, firelight, dawn; for the occasional real danger, not the constant digital kind. It is probably uncontroversial to claim that, compared to other animals, we have a high capacity for data processing. Nonetheless, I fear we have become complacent: no organism is built to witness horror and humour in the same five seconds, to scroll endlessly between catastrophe and distraction. Yet here we are, infinitely scrolling, mistaking exposure for empathy.

The endless scroll, once merely numbing, has become corrosive. Each year the feed grows sharper, hungrier: algorithms tuned for outrage, complex topics compressed into seconds, importance measured in views. What began as idle connection has become compulsion. The distance between a meme and a massacre is now less than a swipe, and every change of image demands a new emotion: laughter, horror, envy, despair. No creature—human or otherwise—is wired for such whiplash.

∞ → funny skit → graphic footage of limbless children → cooking tutorial → side-by-side showing scale of destruction in Gaza → viral dance → yet another country flattened by Western bombs → cute cats → a mother with the remains of her baby → Met gala fits → ∞

The algorithm calls it engagement. I call it erosion. Every scroll feels like a prayer muttered too late—reflexive, guilty, meaningless. The horror doesn’t touch me, but it also never leaves.

Watching isn’t witnessing, I remind myself; yet my stomach still knots at the sight of ruins and the echo of screams I only half-imagine. Empathy used to be a signal to act. Now it’s just another notification.

Thousands of years ago, if you saw someone suffer, they were close enough to help. You could run towards them, or away. Now I sit in northern England with my phone glowing like a wound, two thousand miles from the people I can’t stop watching die. I cry, donate, delete drafts of essays that feel shallow before they’re finished. Powerless, powerless, powerless, I think, until the thought itself becomes unbearable.

Then comes the jolt. The illusion of helplessness is just that: an illusion. Small actions still send ripples, and the butterfly effect, however misused, refuses to die.

One afternoon, after an endless scroll that ends somewhere between despair and catatonia, I stumble on an article. My government—those sleek liars who sign letters in my name—isn’t a bystander but an accessory. Opaque surveillance flights from Cyprus, components stamped “Made in Manchester” bolted to machines that vaporise families. The companies profit, the ministers preen, and the shareholders toast record quarters.

The factories are local. The guilty live within delivery distance. Neighbours, technically. Men and women who clock in, assemble parts, clock out, and call it a living. I imagine their payslips warm with blood.

Online, I see others trying—blocking entrances, chaining themselves to gates, delaying shipments for an hour or two. Futile, maybe, but not nothing. The butterfly still flaps.

So I start making arrangements.

I dress plainly, mask on, cash in pocket like it’s contraband. At the ironmonger’s, I practise casualness, which of course makes me look suspicious. The shopkeeper studies me—middle-aged, grease under the nails, a man who knows a story when he sees one.

“Sledgehammers,” I mumble, pretending to browse. He disappears into the back and returns with two. One feels theatrical; the other biblical. I take the larger.

“Someone piss you off?” he asks, half-joking.

“I erect marquees,” I say, too fast. My face fights a smirk. He takes the cash, the corner of his mouth lifting in conspiratorial amusement.

My new accomplice—a sledgehammer wrapped in a sleeping bag—lies in the boot as I open Google Maps. Fireworks near me.

The place is small, locked, the owner home. He answers after I call the number in the window and tells me to wait twenty minutes. I kill time with a meal deal, chewing as though preparing for trial. When he arrives, I ask for flares.

“Red or green?” he says.

“Both.”

He hands me the packet, no questions, no knowing grin. Eighteen pounds, cash. The quiet transaction feels dirtier than it should.

A few days later, two identical flags arrive. My girlfriend catches the package before I can hide it. She knows the colours, vaguely the meaning, but her algorithm is gentler; her feed still has recipes and sunsets. I envy her ignorance.

I joke about hanging one in the living room window. She reminds me that it’s against the tenancy agreement and possibly against common sense. She’s right, of course. Visibility is risk.

The jigsaw starts to take form. I buy goggles, gloves, a dust mask: items no one would think twice about.

Sleep, when it comes, is frantic. I don’t dream of faces anymore; I dream of maps. Industrial estates, security gates, air vents, rooflines. I know the coordinates by heart. I stalk factory layouts the way predators track herds. My brain runs reconnaissance while my body lies still.

The thrill of potential destruction hums under my skin. It feels righteous, then ridiculous, then righteous again. Powerless no longer—just slightly insane, maybe, but awake.

Eventually my girlfriend runs out of patience. She’s noticed the night drives, the cryptic allusions to future absence, the half-packed bag by the door. I tell her fragments—the sleeplessness, the factory, the complicity—but I can’t say the words that keep me up: children, bullets, silence.

The photo that breaks me isn’t the worst I’ve seen. Tiny graves dug outside a Palestinian school, meant as a warning. Before that, settlers left blood-stained dolls. I can’t explain why this image unravels me more than the bombed hospitals or the piles of limbs. Maybe it’s because cruelty aimed at children makes the mind short-circuit. You can’t reason with such deliberate inhumanity.

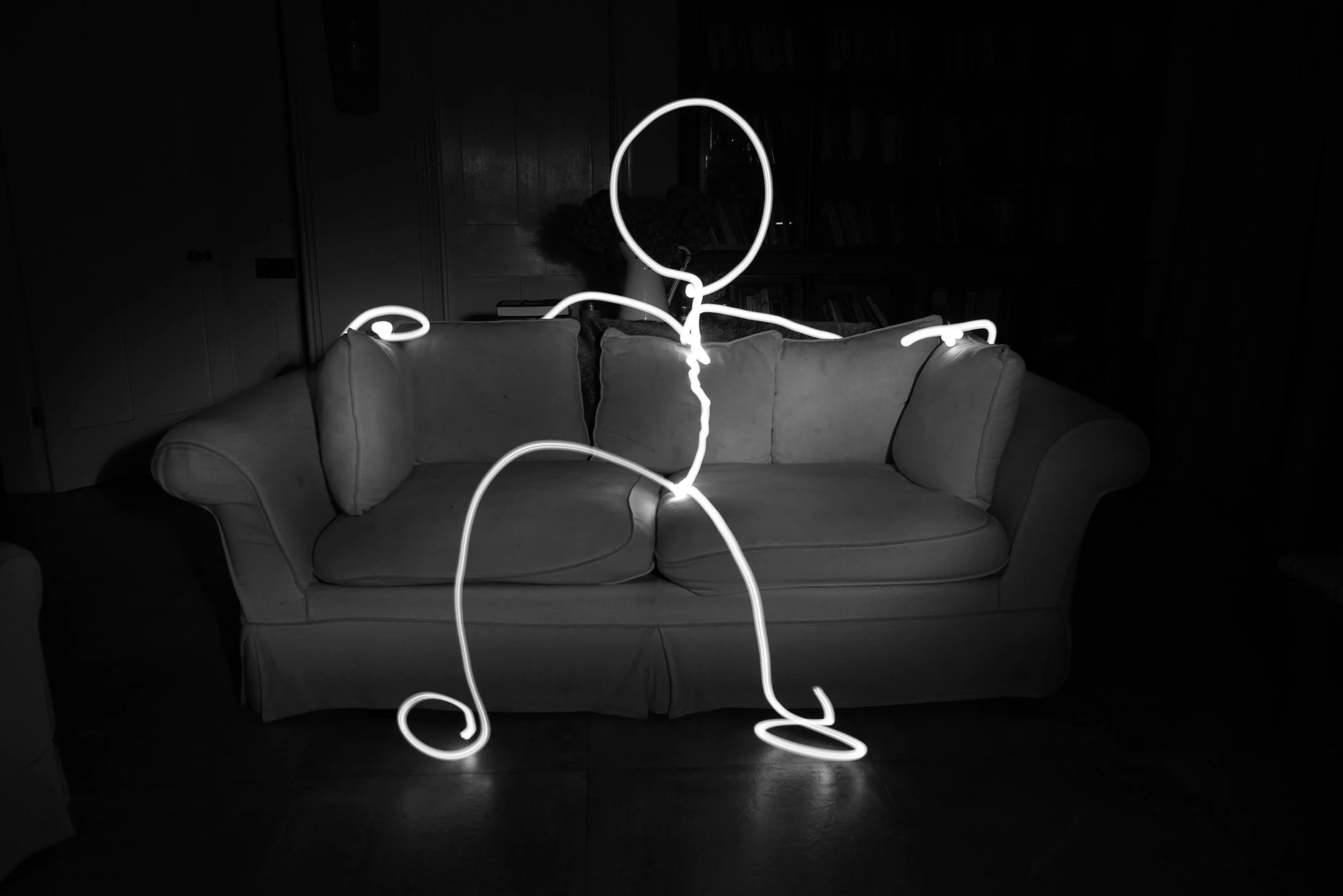

When she finds me crying on the sofa, I don’t have language left. Later, neither do the police. During the interview they’ll ask what pushed me, and I’ll stare wordlessly at the table until they shuffle away in discomfort.

I never marked the date. I didn’t plan it carefully or conspire with anyone. I just knew that waiting was starting to feel worse than doing. People who have never felt that particular moral vertigo can’t understand the relief that action promises.

The day comes cold and bright. I’m scheduled for a medical screening—another clinical trial, another blood draw. Hunger and mild anaemia make me almost serene. I’m already nearby, and the factory I’ve memorised sits just off a dead-end road, practically inviting me in.

I stop first at a tool shop for a bike lock, asking questions designed not to sound like what they are. The clerk sells me a thick chain, probably for a motorbike. He doesn’t care what I’ll do with it.

Back in the car, I shake the spray cans and drive to a quiet lay-by. My heart’s steady, my hands certain. I paint FREE GAZA across both doors, FREE PALESTINE on the bonnet. The letters bleed down like lacerated flesh.

Music blares: Palestinian resistance songs, the playlist I’ll later read described in court documents as “loud Arabic music.” I drive to the factory, windows down, flag ready.

I park squarely in front of the gate, careful not to hit it. The flag tucks neatly into the window frames. The lock snaps around my neck and steering wheel with a satisfying click. The key goes down my waistband. Then I honk in time with the music.

A guard appears, phone already at his ear, mouthing anger through the glass. I mouth a half-sincere apology back. The trapped electrician shrugs at me through his van window; I shrug too, comrades in minor inconvenience. For a moment, everything feels perfectly aligned: my outrage, my fear, my purpose.

Sirens in the distance.

When the police arrive, they pour out of the van like a circus act, batons already drawn. One raps on the window, asks politely if I’ll unlock. I point to the chain. He tries again, sterner. I shake my head.

I’d imagined a standoff, some negotiation, a chance to make a speech. Instead, he swings. Metal screams, glass blooms inward. The sound is magnificent. Another smash, another window. I duck and laugh involuntarily—it’s pure adrenaline.

Whilst he dumbly fiddles with the car door, I ask if he is aware that drones made here are fitted with speakers to play the sounds of crying women and children to lure concerned citizens from their homes and shoot them point-blank in the face; if he feels as disgusted by this as I do. He doesn’t meet my eyes. He says there are “better ways.” I say I agree, but we mean opposite things.

They wrestle the lock, twisting my neck like a jar lid. When it finally gives, they drag me out, shouting for calm while doing the opposite. I tell them, quietly assertive, that I can walk. I even add, “Can we all calm down, please?” which earns me a look somewhere between pity and hatred.

As they move my car, I watch from my human-sized cube in the back, neck aching, wrists burning. So much for disruption. Even so, I feel elated, ecstatic, purposeful. Powerful, in the smallest way.

The officer opposite me in the van isn’t the window-smasher. Younger, cleaner, maybe kinder. He watches me sing Bella Ciao at full volume all the way to the station. I like to imagine he hums along internally, although it’s more likely he’s just counting down the minutes.

At booking, I’m treated like someone rehearsing for martyrdom and getting the tone wrong. I can’t stop smiling; the adrenaline won’t let me. They catalogue my possessions: spray cans, gloves, a half-empty bottle of water, a folded flag. The officer pauses at the flag like it might explode.

The interview room smells of instant coffee and quiet contempt. They ask the usual things—intent, affiliation, funding. I explain that I’m unaffiliated, underfunded, and over-informed. They ask if I regret it. I tell them I regret not doing more. There’s a silence so long I can hear the hum of the fluorescent lights. Someone coughs. Another scribbles uncooperative.

When they ask why, I open my mouth, but the words don’t come. I want to describe the child-sized graves, the blood-stained dolls, the unbearable continuity of horror. Instead I break down, shoulders shuddering with soundless sobs, until the officers leave the room, muttering about mental health.

Twenty-four hours in custody. Concrete bed, wafer-thin blanket, the feeling of time dissolving. I sleep dreamlessly for the first time in months. When I wake, my phone and dignity have been confiscated. They tell me I’m on bail, that I can’t enter the county, that they’ll keep the phone for “evidence.” I tell them they can keep it forever. They don’t laugh.

Outside, the air feels counterfeit. The sky too bright, the pavement too polite. I half expect the world to look different, as if my small act might have shifted its axis. It hasn’t. Cars still drive by. People still scroll.

My wrists are bruised. My voice hoarse. But the tremor that used to sit beneath my ribs—the one called powerlessness—is gone.

Even if they’d locked me away for years, it wouldn’t have amounted to a single drop in the oceans of grief I’ve seen through screens.

Still, one drop changes the tide, if only for a moment.

The butterfly effect exists, and that changes everything.

BIO: Luke Carter is a writer and translator living in the highlands of Guatemala. His work seeks to interrogate the current sociopoliticoeconomic moment whilst subtly hinting at ways of imagining a better world. Translations from Spanish and Portuguese are forthcoming at Chewers by Masticadores. He is scared of X, but can be found on instagram @translations.terrestres