four poems

by Robert McDonald

Fishing

How often will a man dig up the basement of his own house, in order to examine the foundation? And what will happen, when his spade turns up worms the color of milk gone sour, the air weighted with a similar smell? Will he abandon his excavation in order to go fishing? What catch could he land? How shall that behemoth be prepared? What knife in his tackle box can flick off the scales, as reddened and flaky as iron? What sauce might flavor the lightly pink flesh, more pork than a thing of the sea? What dour root, baked, could one suggest, what might compliment such a heavy meal? Does some herb or lettuce grow near the house? Are the foundations yet solid, is the architect proud? Does a man, while digging, ever pause to regard the stumpy soldier, his wicked thumb, and proclaim it the thumb of a very old man? How much of any story is unconsciously withheld? When I dig up my cellar, where shall I pile the dirt, and what will the rest of the family have to say, when they return at last from church? The sermon today was to involve unseen companions, a single set of footprints on a storm-weary beach, and even the fall of a sparrow.

Ten Dozen Ways to Disappoint You

The dark lady laughed again. A sound like crows shouting at the old tom cat in the backyard. The dark lady laughs, at plans, and predictions, at anyone who thinks they know how life is going to be. “Might as well laugh,” says the dark lady, might as well, because there will be sudden and unpredicted storms, there will be flat tires and lousy internet connections. The dark lady laughs; she’s not made a habit of weeping, that’s someone else’s sacred task. When the dark lady laughs, she is laughing at me. The world, she says, will manufacture ten dozen ways to disappoint you: a stone in your shoe, the crash ahead of you on the highway, so you miss your friend’s wedding. Lost set of keys, broken door, fire and earthquake and backed up sewer. It’s not personal, the dark lady says, running her fingers through her silvery hair. It’s not about you, and your deepest desires. Somewhere, faintly, a roll of drums, and the dark lady smiles, all sharp needle teeth. She stamps her foot, up and down, and says “Now it’s time to dance.”

The Thwack of a Fallen Umbrella

The sleeping car had sunk into its night silence, a rattlesome, clanking silence, punctuated at times by the ding-ding-ding of warning signals at country road crossings. The ravens, who had taken human form, stayed upright in the compartment, swaying back and forth to the jolty and bumbled rhythm of the train. Their raucous arguments had ceased: they would follow the Duke’s original plan, and wage guerilla war upon the Moon and her daughters. One bird squawked when his head bumped into the silver luggage rack, but other than that their utterances ceased. By daybreak the train would arrive at the necessary station. Unused to these borrowed forms, one by one they tucked their heads down into the crook of their upraised arms, like a pack of morticians in a deodorant commercial.

The train crossed rivers, and valleys, and entered the long-sought evergreen forest. Some ravens tutted a bit as they settled. A rustle of cloaks, the thwack of a fallen umbrella. At last the fierce birds slept.

Among the Pigeons

We were supposed to have gone to see the moon rise or the sun set or watch on the shoreline as all the tattooed young people drummed in a circle and played with fire. You were supposed to ride your bike so fast that your thighs would ache for three days. I thought there’d be years of climbing up staircases inside church towers, breathing proud exhalations at the top, among the white pigeons of morning. But you do not watch the moon rise. You don’t see slender-armed people twirling chains of fire. You don’t bike, or run, or climb, as far as I know. In the house of memory, the moon is dark, the fireplace cold, and my fingers still feel the soft grit of your ashes.

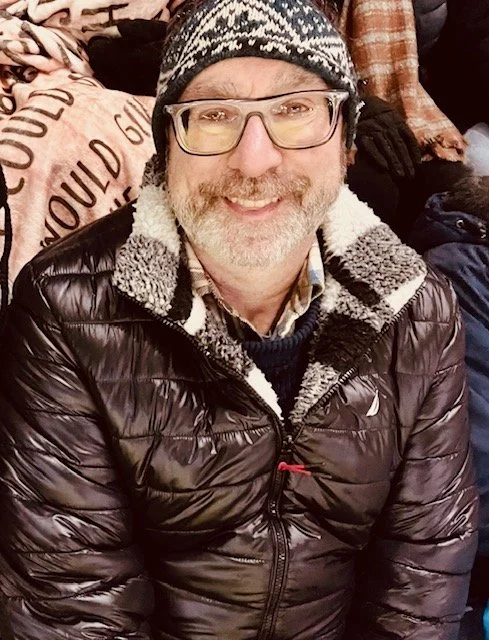

Photo of Robert McDonald

BIO: Robert McDonald's work has appeared recently or is forthcoming in Emerge, Gone Lawn, I-7-Review, San Pedro River Review, West Trade Review, cataloguing poetry magazine, and Action/Spectacle, among others. He lives in Chicago with his husband.