the grandparent scam

by D. C. Martin

Ding dong.

Frederick Telford was completely exasperated. He was on the floor, hands and knees, his lungs filling and emptying. His heart working too hard. Drops of sweat speckling the floor. This’ll be another heart attack, he thought. I’ll be sprawled out here, on the basement floor, that’s how they’ll find me. His doorbell rang again and he finally got to his feet by steadying himself on the workbench. There was a little blood on his undershirt, so he buttoned up before taking the stairs. One step at a time, he reminded himself. He looked back down the stairs and thought about all the things that got him here, before it got fucked to shit. Yesterday actually started very well.

“Look, Mr. Telford. Look at me!” Janey yelled out, thrilled. She pedalled through the sharp turn at the bottom of Elmdale Avenue.

“You’ve got it, Janey! Just look at you go!”

Robert, her father, nodded back, looking up for a second. Then he quickly set his focus back on the wobbly bicycle. Sweat poured down his face, and his tucked-in button shirt was so soaked that you could see a blue-green tattoo on his shoulder, dripping down his back with age.

Telford closed his eyes as they pedalled away, wishing he could feel what Robert felt. That memory, that joy. But he was all alone now. He wondered at that for a moment. Whether or not he had ever had joy, a joyful moment. The closest he ever came was all his time with her, his wife. And she was gone. He was afraid of losing her face, like he lost the sound of her voice, her laugh.

He was terrified about losing more of her but kept testing himself. He made his mind into plain white, just an eight and a half by eleven frame of white and he put her eyes there. Shiny and brown, kind of sad. Her lips came next, each dot, each wrinkle, each hue. Her face spread out on the blank sheet, expanding from the center until he could make it smile. He got lost there, as he often did, haunted by her eyes. But he had them, they were his forever, not only in his memory and in photographs. They were his, and he could touch them. They were locked away, and he was the only one with a key.

Her smile lit up a room. It was the reason that he could be shy and awkward. Everyone was always so happy to see her, and he could disappear into the background. All he needed to know was how to get back to her. And he felt sorry for himself. He felt like he had no business being with her. So smart, so natural. Everyone loved her.

“I love your wife.”

He heard it countless times until it echoed in him, even his dreams. She was so charming, she was so witty, she was so pretty. Her outfits, her purses, her shoes. He always faded in her radiance. But he saw the light that others cast on her. He saw her glistening with the shine of their desire. She could have found someone a lot better than him. He knew it, he lived with it.

And she knew it, too. He was never good enough for her. She would run him down about it all the time. Comparing him to the other husbands from work. Why wasn’t he more active? Why didn’t he play golf, why didn’t he go jogging, fishing, camping? Why didn’t he? But he was plain and he was boring. He was inadequate, and she was deluded. She always wanted whatever she couldn’t have, like those other husbands. Those men who liked golfing, jogging, fishing and camping. Fools who would ignore her to go off on a pointless adventure.

Loneliness set in over so long that Telford had no idea of its power. He would take long walks and stop in places, ones with a connection to her. This is where we stopped because she lost her keys and we searched everywhere in the snow—they were on the kitchen counter all along—this is where she stopped when she found out her mother died.

“But she…she was doing so well.”

This was where they gave up on having a child.

“We’ve still got each other.”

Those broken pieces of him ran through his mind no matter how hard he tried to ignore them. Their shards pressing in on him, making each moment a painful reminder. Making it impossible for him to enjoy a sunny day or the sight of a little girl learning to ride a bike. He rose from his Muskoka chair and went back inside, screen door slamming behind him. He washed the dishes. Routines made his days sufferable. Next stop was the shower.

He watched the condensation on the glass door form tiny drops, each holding its own place, even as they bulged with weight, until another falling drop met it, and dragged it down. He wiped the mirror down and looked at the tired old man, only a shadow of the man she fell in love with.

“I’ll be with you soon, my love.”

Telford stopped, as he always did, at his favorite picture of her. The one in the front hall. He remembered the first time he saw it. He was flipping through all 24 prints from the Fotomat and stopped, shocked. She looked like a goddamn model. He actually took the picture by accident, as she was turning away from him. It was from their trip to Florida, and he had just taken a picture of the sunset and started reeling the film. His thumb slipped and, voilà! Artistic genius. Her expression was as easy to describe as The Girl with the Pearl Earring’s. But he knew what it was—acceptance. Grudging acceptance. She could have done leagues better. They both knew that.

Staring into an old photograph doesn't fix anything. Just makes things worse. Undoing the past is impossible. And yet, there he was, this worthless old man, staring deep into the black pupils of her eyes. They were beautiful, so beautiful.

Smash!

A baseball came through the front window.

“Damn it!”

He swung the screen door open so hard that the handle left an imprint on the front hall drywall. A bunch of kids ran away down the street, laughing. He picked up the ball and held it, felt its weight. He moved quickly and almost tripped on the porch stairs, catching the railing just in time.

“Damn it! You get back here!”

He looked down at the scuffed-up ball, barely held together by a few remaining threads. It wasn’t too long ago that he was there, one of the boys in the street. Did he run away? Did he laugh?

“Go on, Freddy, your turn.”

All the boys pulled in, ready to catch something in the infield.

The pitcher threw the ball so hard the nine-year-old Telford jumped back. There was lots of laughing.

“Strike one!”

Telford just wanted to shut all of that out, get ready to hit the next pitch.

As the ball was hurled towards him, Telford had a moment of clarity, and everything slowed down. He was going to hit it, he knew it.

Crack!

He hit it hard, too.

“Foul ball!”

Smash!

It hit his neighbour’s window. All the other kids ran away. He just stood there. He couldn’t move.

Ding dong.

“Sir, I am sorry. I broke your window.”

“Did you, now? Why didn’t you run away?”

“Well, I, um…”

“Freddy Telford, I appreciate your honesty, but your friends all ran away because they knew you wouldn’t. You’re going to have people take advantage of your trust all your life if you don’t stand up.”

It wasn’t the same for him—he didn’t hurt people. He returned to the kitchen. He gripped the baseball hard before letting go and setting it on the kitchen counter.

Telford became aware of the bottle of beer in his right hand as a drop of condensation hit the patterned, yellow and brown linoleum kitchen floor. The kids had taken their time. Waiting for a moment when he wasn't on the porch. They were taking advantage of him. He became so tired of it all. The illusion. The thing that said he wasn't just a sad old man who sat on his porch all day, waiting for death to take him. That he wasn't just a lonely soul that people should pity, that he wasn’t just the maker of his own ruined destiny.

But he lived their worn-out fantasy and played his part. He was, indeed, a gentle, lonely old man. He was Laurence fucking Olivier. He fell back into his Muskoka chair, set his outdated, irrelevant beer on its arm, twisted its cap and flicked it away into obscurity. He watched a young woman run by, graceful. Poetry in motion. A young man ran past, too. Clueless.

He glanced at the identical chair beside him. Its emptiness, its gravity. Its permanence. Her chair would always be empty. He needed to find the strength to accept that reality.

The phone rang and he sprang to answer.

“Hello?”

“It’s me. I’m in trouble, Grampa, real bad. Grampa, I need your help, please.”

Telford took a moment and said, “I want you to think about the people you hurt doing this. I want you to stop.”

Click.

There was more to his life than this. There was more to this man than a bunch of fading memories, more than the glory days of the past, more life to live. And it would start now. He threw back the contents of the bottle and went to get another. This was the moment that made his life change. He was going to teach someone a lesson. The baseball didn’t need to smash his front window, but it…

Ding dong.

Telford was genuinely startled. He looked out the front window and saw a young man. He was dressed quite formal but wearing a toque. For the life of him, he couldn’t figure why anyone would ruin a suit with a toque, not to mention the fact that it was quite warm.

Ding dong.

“Good afternoon.”

“Thank you, sir. And good afternoon to you, too. I represent The Global Human Fund. I am here today to ask for your help. Together we can end the unhomed crisis.”

“Please come in and sit down. My name is Fred.”

“Nathan. Nice to meet you.

“How can I help?” Telford gestured for the young man to sit at the kitchen table. He was hoping that his tone was genuine, but it was difficult to seem sincere right now.

“A modest donation is all we need. We at The Global Human Fund are non-profit. In fact, I am canvassing your neighbourhood voluntarily. I suggest you just give us a toonie or something. If you want a tax receipt, it’ll have to be at least twenty bucks.”

“I’m sure you have all sorts of accreditation, cards and such. A mission statement, some literature about The Global Human Foundation.” Fredrick Telford threaded his fingers into a nest on top of the coffee table. This was the perfect opportunity.

“Fund. It’s The Global Human Fund.” The young man paused, “And, yes. Of course I can produce documents, if you like.” He took out his phone. “I’ll get them to you right away…”

“That’s not necessary. I—”

“Here they are.” The young man turned his phone to Telford. The letters on the screen were very small. Telford produced his reading glasses.

“I can spare twenty bucks. Give me a second to find you a green queen.” Telford rose to his feet and started ascending the stairs.

“Sure. But before you go, we could do this the easy way.”

“Huh?”

“Well, sir, if you prefer, I could just set up an e-Transfer,” the young man punched his thumbs into his device.

“It won’t take a moment for me to find my chequebook.”

“If you like.”

Telford began up the stairs again and turned back. “What would the e-Transfer® entail?”

“Just a few details, sir. Do you have a credit card? We can deal with all of that at the end, and there is no pressure to decide today.”

“Certainly.” After some digging in his wallet, Telford placed a card on the table. “I’ll be right back.”

When he returned, Telford proudly set the perfect charcuterie tray on the coffee table. It included a few slices of American cheddar, some pickles, and three slices of summer sausage rolled up. Telford poured tea, and the kid pored platitudes. Politics, philosophy. The conversations were “deep.” The kid’s eyelids fluttered and he breathed in deep. Telford couldn’t help but notice that his card was now upside-down, with the CVC number clearly visible.

He was completely innocent, the missus would say. Why would you do anything to hurt this innocent young man, the missus would say. But when does it end? How much can we give in to criminals? At some point, someone needs to be taught a lesson.

Let it go, she would say. Words of wisdom.

The kid finally woke up. He looked worse for wear. Telford was prepared for the lesson, he had thought of everything.

“Feelin’ a little outta sorts?” Telford began, “That’ll be the drugs.”

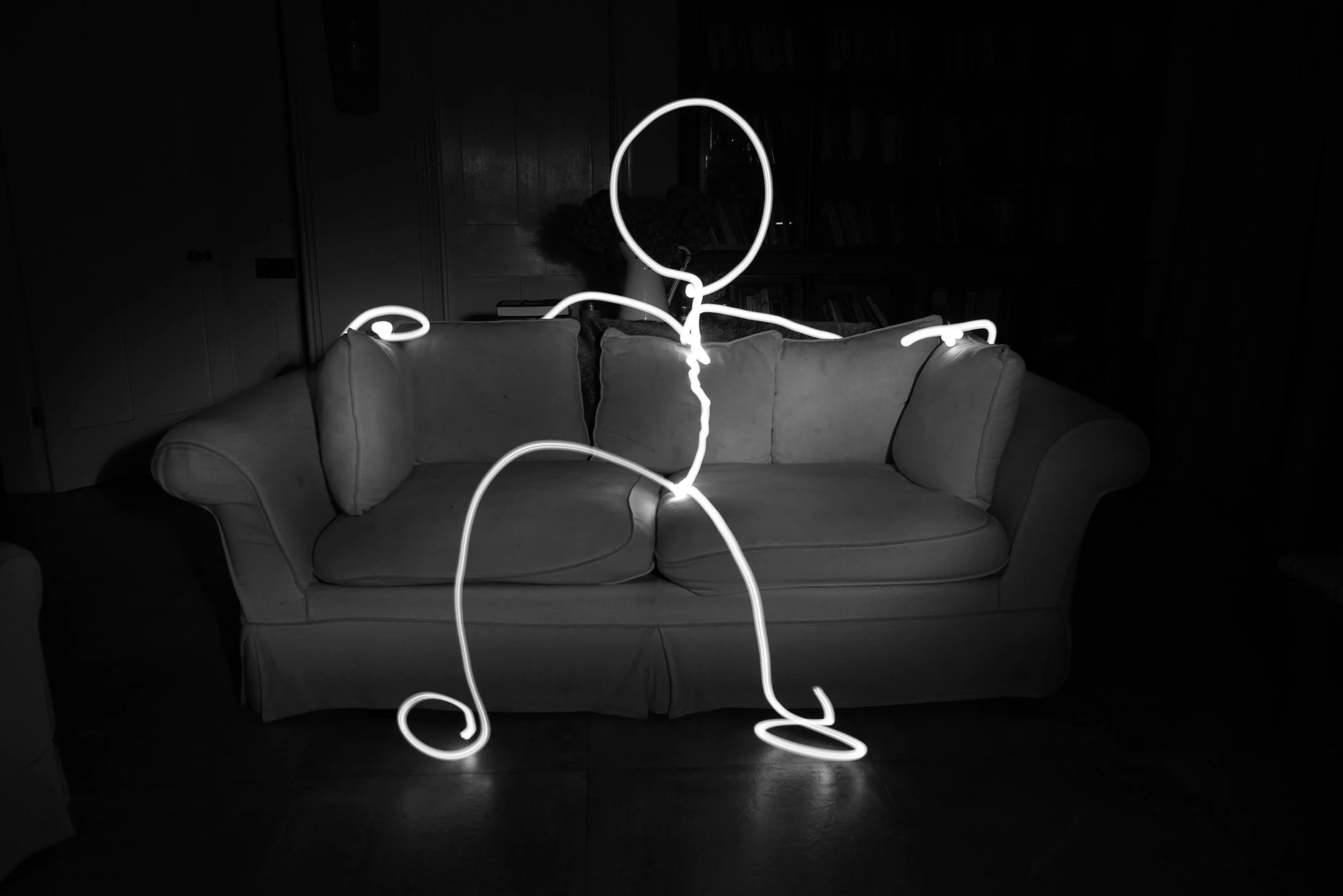

Frederick Telford walked around the young man over and over, spinning his web. He could see the kid’s eyes panning the basement and then staying fixed on the stairs.

“Know what this is, kid?” the old man asked.

The “kid” barely had the strength to look up, but when he did, he saw the old man drop a black plastic case onto the table in front of him. It made a great boom and dust rose around it. Its handle clicked back against its plastic shell.

Telford opened the case, with the lid in front of the kid so he couldn’t see, building suspense. He kept the item from the case hidden behind him, as the kid shivered and shook. Telford placed it behind his back and walked slowly behind him.

“Let me introduce you to my friends, Smith & Wesson.”

The kid was breathing heavy. Panting, with terror in his eyes, but still holding it in pretty good. Telford returned to face the kid. “Before you piss yourself, my friends’ names are actually Black and Decker.”

As he revealed the weapon behind his back, the kid's eyes went from fear to horror.

“This here, this is a nail gun. It’s powered by a little tiny battery, and my wife would get at me and say, ‘Why didn'tcha get the bigger one, or the better one? Or why didn'tcha.’”

Telford stepped forward a bit. “You’re getting bored. I’ve bored you with my anecdote about the wife, I see. She got bored, too, she got bored alright. But never again.”

He stepped away and aimed the nail gun at the wall. “Perhaps you would like to see a demonstration.”

The kid didn’t respond. Telford walked behind him and observed his chest heaving, his shoulders moving up and down, his whole body shaking. But the drugs kept him pinned to the chair.

Telford approached the shaking kid slowly from behind, the barely audible squeak of his feet gently gripping and releasing the basement floor the only sound. He pointed the nail gun at the back of the boy’s head. Telford could feel the wall of the kid’s skull through the handle of the nail gun.

The kid got all startled. His breathing was quick and sniffy. Telford put his hand on the kid’s shoulder, and he jerked up into a tense posture. The lesson was very effective so far.

“Observe the demonstration.”

Telford returned to the middle of the room and observed that the kid was now unable to keep his mouth from being agape, unable to steady his breathing.

“See that picture of the wife over there?” Telford aimed the gun at the wall, at the photo, just to the centre of his wife’s head.

The kid didn’t want to look. “Look here, kid. That’s my wife, the missus. She just retired. We had a big party. You like parties, kid?” Telford put a couple fingers under the kid’s chin and tilted it into the correct viewing angle.

He aimed the nail gun from a distance, about nine feet, and fired. It hit the mark and the glass shattered around it. The frame and the glass pulled apart slowly, while the picture stayed fastened to the wall. Finally, the bottom edge of the frame dropped, pulling the rest of the photo down as the glass smashed on the shiny concrete floor.

The nail had gripped the drywall but only went in halfway. ’Course it wasn't really the missus. Earlier, he searched for “creepy old-timey portraits of ladies” and printed a high-res image of the sixth thing that came up. He put it in the fancy-looking frame he bought from the Value Village while the kid was snoring and drooling on the floor.

“It’s really only a pin hole,” Telford said, as the kid jumped and went into some pretty turbulent twitching and sniffing. Next, he walked over to the wall and stuck the nail gun against it and pressed the trigger. A nail penetrated the wall fully, head flush with the paper edge of the drywall.

“And now,” just approaching the kid made Telford realise why they always gag people in the movies—the kid let go of everything, and it was very loud. Telford himself almost puked as a reaction. He felt a moment of self-doubt but chose not to beat himself up. He was new at this, but he would learn quickly.

The kid fell to the floor. It was clear now that he needed to be restrained.

Zip ties.

The zip ties wrapped around the kid’s wrists and ankles. Very effective.

Duct tape.

That goes over the mouth. It doesn't create silence, but muffled screams are easier to take, like all those warning sounds in your car with the radio on.

Telford cleaned up all the puke and waited for the kid to wake up. He should have known to use the zip ties, he should have known to use the duct tape. He could see her disapproving glare, he could see her walking down the basement stairs, yelling at him, running him down. All a bunch of “Why didn’tchas and ya shouldas!”

And he aimed his Black and Decker and shot over and over as the missus somersaulted down the steps, bloody and broken at the basement floor. The kid was startled awake.

“And now, I will show you how the nail gun goes straight through a femur.” He pressed it against the kid’s thigh. His breathing quickened, tears poured out of his eyes. His nose was pushing out big globs of snot and sweat was dripping over his duct-taped jaw.

The gun clapped its “click, clack” sound loud and a steady stream flowed and dripped to the floor. Muffled screams emanated underneath the duct tape. The kid calmed a little and realized that his leg was the same as it was before. He looked at the old man with a bewildered, beholden gaze.

“Outta nails, kid.”

Telford loosened his grip on the trigger of the Black and Decker. He walked backwards as the kid pressed desperate screams against the sticky silver wall of the duct tape. He saw himself in the kid’s eyes. He was trapped, too. Trapped by loneliness and self-loathing. He needed her, she was the only reason that he could ever stand up. She taught him how to be a man. The man that he was made her proud. It made him proud, too. What happened to that man? What happened to the courage he had?

“You’re not beneath anyone. You are worthy of everyone’s respect.”

He talked to people. He initiated conversations. He had moments when he was the most charming man at the party. When he would look back at her and she would see the best of him.

“I love your husband.”

Without her he was an old man terrorizing kids for nothing. For his own twisted amusement, for his misguided sense of justice. For revenge. It was payback for every broken window and every burning bag of shit. Every entitled asshole that ever laughed. Every prick at every Christmas party that looked at her and then him and wondered what the hell she had gotten herself into. But this kid hadn't broken his window. This kid only wanted to break his bank account. And who could blame him, rules don’t exist anymore. Respect doesn’t exist anymore. Righteousness is dead, buried in between morality and honesty, Rest in Peace.

Telford went upstairs and flipped the cap off a bottle of beer. A little foam crested the lip. He went to his favorite place in the world and placed the bottle on the arm of his Muskoka chair.

“Damn it.”

He closed his eyes and listened to sounds near and distant. Birds sang and the breeze whistled. Dogs barked and the engines of cars hummed. Feet plodded and leaves rustled. Before he could take his first sip, he heard something from the basement. He put it off as his own paranoia, it stopped. But then there was a loud bang, and he ran over and burst the door to the basement open.

As soon as he did that, it sent the kid backwards down the stairs. He had made his way to the top running, and the door smacked him hard. Telford ran down to help, but he’d broken his neck, not to mention the serious gouge on his forehead, spilling blood rapidly. Telford held the kid and looked for any sign of life. He was young, just starting out. What did this damn fool get himself into? Now he was dead. Dead on the spot.

Telford looked at his workbench, tools scattered everywhere. It really worked, his scam. The kid really bought it. If only he stayed down there, if only he had the chance to explain. This was supposed to be a warning, a lesson. He lay the kid down gently; he was already ashen white.

“I knew it was a scam, kid. Knew it all along. You’re not so bad. I’m really sorry it turned out this way.”

He started examining the room, curious about the escape. Somehow, he got to the workbench. The chair was there, on its side.

“How the helld’ya get through those zip ties?” Telford said out loud as he looked over at the pegboard above the workbench, where every tool was always put away on a hook surrounded by its Magic Marker outline. The needle-nose pliers weren’t there, but on the floor, open.

“I coulda stepped on these, kid.”

Fredrick Telford took a long time to prepare, but he was ready to take a trip to Blackfork River, just north of the Aberdeen Camping Resort. He loaded his cargo into the trunk in a blue tarp. He hoped people would assume that the kid fell down a hill. It was all possible; he hadn’t used his phone in hours. He could have hitchhiked there. Telford just couldn’t stomach any other way to get rid of him, so rolling him into the river would have to do the trick.

Thing was that hauling the kid up the stairs and then into the car was a big damn pain in the ass. He couldn’t stop sweating, even though he felt cold. He couldn’t calm his breathing down, but he couldn’t get enough air. It felt like he had an anvil crushing down on his chest. He had to get out of the car and get some fresh air. He was able to open the door, but stopped there, trying to breathe in the summer air, his jaw throbbing in pain.

This was the end for him. His miserable life was over. They’d find the kid in the trunk, and they’d think that he was a killer. A force of evil. A ruined man, a bad man.

“Hey, are you alright in there?”

Somehow, Frederick Telford opened his eyes again. There were binging sounds and muffled announcements. Telford was only worried about the contents of his trunk and disposing of them. He was in the hospital with some young man in a satanic rock T-shirt, the one who found him after the heart attack. The guy even drove him home.

He was a nice enough guy, but Telford worried that he might come back. The last thing he needed right now was someone sniffing around his house. He wanted to get back to cleaning up his basement, and then his solitude. He was using a particularly aggressive chemical solvent—which could eat through anything. Every item in the basement was going to be put back just the way it was supposed to be.

Ding Dong

The damn doorbell again. Telford climbed the stairs quick. He opened it and there was a kid with the same outfit as the other one—The Global Human Fund.

“You already came to my house yesterday,” Telford said while closing the door.

“No, wait.”

The kid’s foot was in the door, but it seemed like he didn’t know what to say. A yellowjacket buzzed around the porch and joined its friends under the front steps.

“Sorry, sir. I hate to disturb you. I’m looking for Nathan.”

The kid walked in zigzags in front of the house with his phone in front of him.

“It’s just. You know, I got a ping. He pinged here yesterday.”

Telford had never heard of a ping. This was enough, though. Enough to want to quash the young man’s interest.

“Ping, eh? We better go inside. Better not to risk it.”

The screen door slammed closed and the kid with the pinging phone walked through the house. He turned right and proceeded down the stairs.

Frederick Telford followed him and locked the door to the basement. He wished that all of the people who hurt him could see. All the boys who pulled in closer when he got up to the plate, all the husbands at all the parties who looked down his wife’s top as she assembled her plates at potlucks, all the kids who sneered as they rode their bikes past his porch, ready to break windows. All of the assholes who phoned grandparents pretending to be grandkids and extracted thousands for imaginary bail money. This was for them; they needed to see.

For a moment he thought about her. And he would do it right this time, she would see that. She would see how much better he was, how much stronger. He barely resembled the man he was, back when he had her, back when he lost her. He had found her sprawled out on the floor face-down, ruined.

The first thing Telford noticed was her drool. A shiny dot reflected the main hall chandelier’s light from the centre of the gradually expanding pool of spit on the textured pink carpet in the living room. Then he noticed how smudged-up her makeup was. She looked wrong.

“Sandra?”

He put his hand on her shoulder. He squeezed a little. She was cold. He jumped back.

“Sandra?”

He fell to the ground and breathed out hard. He looked at his hand. It shook. He looked at the wedding picture in the front hall in front of him. It shifted to the right and came back again. It wouldn't stay still. He sighed.

He glanced over at the occasional table. It had a bottle of Loch Lomond Eighteen-Year-Old single malt knocked over and tragically empty. Her retirement party was wild. Telford was still drunk.

He tried standing, but the pink carpet gripped him like velcro. He picked up her hand, and it snapped back dripping crimson from her wrist onto the pink carpet. Each drop became an hour, each moment became a year. She cut herself deep and was drained of all life. He should have called the police. He should have sobered up. He needed to hide this, he needed to hide this for her, to preserve her dignity.

He reassembled her face, bit by bit, from his memory. She was beautiful. Telford opened the chest freezer and looked at her again, gaining the strength he needed. The basement was messy with the first kid, and the second kid was starting to freak out. Breathing heavy, looking very fight-or-flight. He slammed the chest freezer door down and turned to face the second kid.

“It’s okay,” Telford said. The kid’s legs were wobbling, his breathing was frantic and he was shaking.

“I, I…”

“Sure. Take your time.” Telford still couldn’t look him in the eye.

Telford thought about whether or not he should get to Blackfork River by way of the Twenty this time. Was there still a detour through Sheffield? And where can you buy a damn tarp at this hour? He went over to the workbench and considered which tool was right for the job.

The kid fell to his knees and took out his phone, but his hands were shaking so bad that he couldn’t even open it. Telford kicked it away with his boot and it skittered across the floor towards the chest freezer. The kid looked up at him and squinted at the light. Telford saw himself in the blinking reflection of the kid’s eyes. An angry old man with a sledgehammer raised above his head.

“You don’t have the balls to do it,” the missus would say.

Crack!

BIO: D. C. Martin is an emerging writer who lives in Guelph, Ontario. He hates the winter and people who don’t signal lane changes. His writing is known for its quirky, endearing characters who find themselves in highly unexpected predicaments. Mr. Martin teaches Grade 4 and lives with his wife, daughter and cantankerous cat.