an odd thing

by Chuck Strange

Terry saw Donna the first time when he was driving around town with the radio on looking for something. It wasn’t a sign he was after, Terry wasn’t sentimental. Terry was 40. He wanted to see a spark, something from the old life. A shirtless kid on the sidewalk dragging a wagon full of fishing poles could have done it. Or a shoeless toddler with wing droop bawling on a stoop over a splinter in the big toe. Seeing the right bird in the right patch of grass had held him over before. And this was the time of year when the fat bellied robins had taken over.

At home Terry’s wife baked lemon loafs and shopped online for cordless vacuums. She found out her step sister was going to Aruba with her fiancé and then she started getting beat over the head with Instagram ads for the all-inclusive packages on sale.

“But I don’t know what we’d do with Lorraine,” she said every time the right equation of sun and sand on the screen gave her the melt.

“There’s a dog kennel in Kingston,” Terry told her.

“You’re horrible,” she snickered and smacked Terry on the arm with a limp hand.

That day Terry was driving around, the trailer park on Court Street was having its annual spring clean out. All the trailers and rotten-tired RVs were stacked into the grass lot off the state route like so many loaves of bread rubbing elbows on the shelf at the grocery store. Donna was pale like a sun bleached shirt, her arms and legs were skinny and firm. You’d lose if you made a money bet that she weighed more than a buck 10. And you could tell she dyed her hair black. Her scalp had a more reddish color erupting from the follicles that looked like withering switchgrass.

She was seated with two people older than he was but not by much. Their harsh lives weighed their heads down and they slunk in their summer chairs near the door of one of the trailers. There were two of those plastic tables and one child’s picnic table with flaking green paint in front of them, full of their wares.

“Donna,” the older man said, nudging the girl up and eying Terry’s steps toward their sale. Terry picked around the stuff at the tables and took big long sniffs with his nose, though he tried to make it subtle. After every deep whiff he’d pinch his septum. If anyone asked he had the word “allergies” loaded and ready to go. He wanted to catch her scent. Something fruity or something strong. Something bad, even. Just wanted it to be hers.

“How much for this?” he asked.

“Let me ask my pa,” she said, rolled it out over a big tongue housed under snaggleteeth. She hadn’t even made eye contact with him and then she was bouncing back over to the trailer. Terry looked at what was in his hand. It was a snowman salt shaker holding a broom but the part you sweep with was broken off.

“You can just have it,” she said as she walked back over.

“That’s mighty kind.” Terry tossed it in the air an inch or two and caught it again. “Think my daughter will like it.” He tried a smile out. She returned a reflexive polite one and studied her shoes.

On his way to the truck Terry heard a man talking at the next trailer. He looked over when he heard him say “cherry red lipstick.” The guy had leather skin, a bald head and a Salt Life tank top resting on his beer belly like a table cloth on a beach ball.

“She drives me nuts with that cherry red lipstick,” he said to a customer. The customer had that look of a man who wanted a way out. “Yep. We go out to eat three nights a week and she gets all done up. Wears sun dresses and heels.”

“Is that right?” the customer said. He was fiddling with CDs on the table between them.

“She used to date a guy who looked like Dolph Lundgren.”

“I don’t know who that is.”

“You don’t know who Dolph Lundgren is? The Nazi guy in Rocky?”

On his way home Terry threw the snowman out the window and watched it burst on the concrete in the side mirror.

Katy, Terry’s wife, was beautiful all the way through, her guts to her eyelashes. Terry loved her the way American men are supposed to love their mothers. When they’d go to school plays or the odd date night dinner, Terry would look around and wonder if they could tell. If they had any idea what sort of trouble Katy pulled Terry from when they met. Probably not. He had the big job in the city, where he made enough money to send Lorraine to catholic grade school. And Katy got to wear flowy dresses while she watered the plants.

A few weeks after he saw Donna he was in the backyard with Lorraine watching her work on the balance beam he’d set up for her. Lorraine was, according to the coach, showing real promise for a girl her age. The coach had leaned into him when he picked her up from practice when she told him. “And between you and me,” she whispered, “I don’t say that to every parent.”

He watched her do the bending and springing around on the beam and encouraged her as she looked up to him for approval after every maneuver. In the window above them he caught Katy watching but pretended not to know she was there. What Katy wanted was a birdseye view of the family she carved from rough stone. If she knew he was watching it would have ruined it. She wanted to see the man she pulled out of the dump like a couch with cigarette burns and lice, took home and made into a foyer centerpiece. And she had done that with Terry. Cause when she got with him, he was at that crossroad every hurt young man gets to, where if he didn’t find something to cool him out he would’ve been liable to set the entire world on fire just so someone would know he’d been there.

“That’s awesome, hunny,” he told Lorraine after she did some sort of springing thing off the bar and put her hands to the heavens in an elegant way. He leaned into his celebratory affect with his body to really drive home for Katy just how beautiful their life was. In the morning he would be on sales calls with the dealer in Syracuse, closing the final deal of the quarter that would get him the 10,000 dollar bonus. In fall, he had designs on taking Katy to Tahiti. Tahiti’s reviews were better than Aruba’s.

The window came open with a screech as the dry plastic rubbed against the dry plastic that housed it. “Guys, lunch is ready!” Katy said.

“Oh shoot, you scared me,” Terry said. “I didn’t even hear you open the window.”

“Five more minutes, mom,” Lorraine said.

“OK, sweetie. Five more minutes. Then come in to eat.” Katy started to close the window then stopped. “You too dad. I made iced tea.”

Terry closed the sales call by 9 a.m. on Monday morning. At noon he pulled the phone from his pocket, texted Katy: “Working late. Gotta get this deal closed. Don’t wait up.”

She still sent hearts the way they used to: <3.

He could barely eat, and he spent most of the morning sitting on the john coaxing himself and his heart back down. By noon his throat was sore from swallowing so much mouth sweat.

Just before dusk he got to the trailer park. He idled in the general lot at the front, maybe a few feet removed from where he’d parked his truck when he first saw her. It was raining and he had the windshield wipers going with the truck running to keep his line of sight from warping in the droplets filling up his windshield. The one room window he could see had a light on a side table and some sort of design on the wallpapered walls. It was just not enough to tell for sure if the room was hers.

He sat in the truck and the radio was on. It was on the country station, and though he didn’t care for music or lyrics he kept it on that station because that’s what men in trucks listened to. He was thinking of the music that used to be going over radios in the old barn parties, back before Katy. But the recall took up too much of his brain and it yielded nothing more than a far off, nameless hum. When he looked back up it was coming down like wet bullets and the light in the room of the trailer was out. It might have been her who turned it off, and he missed it.

“Damn it!” it was an involuntary, guttural yell, and he punched the dash. It cracked under his fist. Katy would notice that and get worried. “God fucking damn it.” He went to hit it again but thought of Katy’s wide eyes when she saw the dash of his truck smashed to pieces. He thought of different lies. Someone had broken in and smashed the dash and left, as a prank. Or he had stomped on his brakes so hard he drove his own head through the dash. But then he’d have to rough up his face. So he pummeled his thighs with hammer fists until he felt his muscles going soft like old apples, and then he gave himself a couple short rabbit punches until the feeling receded. But it wasn’t enough to really sell. He decided it was a break in. Probably teens. Then he put the truck in drive, looked both ways, and turned back onto the state route and went home.

Terry told Katy they were going to Tahiti not long after that. He told her that he was going to make sure they got the best all-inclusive package, that their trip would blow her step-sister’s out of the water.

“Dinner on the beach every night,” he told her. “Way better than Aruba.” Katy bounced around the house weightless after she heard the news. She dusted off the elliptical in the garage and started buying those SlimFast shakes. The catch was, Terry told her, he’d have to really step up at work to secure another bonus. That’s late hours. Katy would have to run Lorraine back and forth to gymnastics for a while. Katy daydreamed of a size zero bikini and those frozen cocktails from a poolside bar like she’d seen in the ads. Terry could have told her he’d be sent to war in the desert on a three month tour to pay for it, and it would not have changed the scenes of blue skies and warm green salt water that played inside her head like movie film rolling along between her ears.

Terry caught glimpses of an arm or a leg, a ponytail through the window, and he’d be fixed for a couple of days. But the quick glimpses stopped rendering. It grew to almost five nights a week by mid July. Terry drove back and forth on the state route, parking at the trailer park for 15 minutes or so and then pulling back out in the flow of regular life before doubling back for another shift on watch in the lot.

They were leaving for Tahiti in the middle of the night on the last Thursday in August. It was Wednesday evening and Katy had taken Lorraine across the county to go stay with her parents while they were gone. Terry thought if he didn’t finish it, he’d never be able to sit on the beach and sip the margaritas. Katy had gotten herself into beach trim, though he thought her newly tight head skin made her look like an imposter. She’d been trying to fool around with him for months, but he couldn’t get past her shrunken shape.

“Save it,” he’d say to her, real cool as they lay coiled in their bedroom. “Save it for Tahiti.”

After he’d given Lorraine a big hug and a kiss and told her how much he’d miss her, he waited for the ambient buzz of an empty house to set in before he got his keys. From their cul-de-sac the last reams of sunlight were doing goodnight stretches from behind the many perfectly constructed homes of his neighbor’s. As he pulled out he waved to Mike, a dentist who stood at the front of his driveway, watering sweetgreen grass. On the radio a cowboy sang about a broken heart. Homes stacked into the hill deteriorated in strips, like a tornado had gone through passively on fourth street, mad on third, vicious on second and evil on first. On the state route there were boys on bicycles, pedaling toward something dead on the shoulder of the road.

He made his usual route, from the trailer park to the Dollar General and back, when he spotted Donna’s bright white legs in his headlights. He could feel his heart slamming in his eyes. He eased the truck off the side of the road in front of her, watched her in the rearview mirror. She hadn’t noticed him pull over, she was watching her pigeon feet go along the roadside gravel with her headphones on.

Terry bit his lip to try to keep his heart from exploding. He bit so hard he drew blood. But his heart was going at a wild rate, the world around him was swimming in all that coming dark. He bit down harder and looked down to the hand bouncing on his thigh, drops of blood coiling into his arm hair. He rubbed his chin with the back of his hand to stifle the drips.

He rolled his window down just as Donna approached. She watched the window come down and took her headphones off, stared up at the man like a deer lost in the headlights on some rural road. Terry swallowed and thought of what to say. Donna fiddled with her shirt as she came up to the window. His chin was covered with thick ropes of blood. She drew a hand up to her mouth to cover a gasp.

He went to speak but his tongue was swollen in his mouth and the vowels wouldn’t form. She took a few steps back. Terry put the truck in park and unlatched the door. Donna ran. The door of the truck swung open. Terry jumped down into the gravel. He watched her go, getting smaller with every step down the gravel shoulder of the state route. His feet shuffled after her and then stopped. It was just about black with night, and he could barely make out her shape as she went off, only hear an echo of small rocks rubbing under her feet. Then a car crested the horizon, its headlights bringing the faintest picture of Donna’s frame back. Once the car passed her all Terry could see were those two big, blinding orange lights. They closed in on him rapidly, bigger and bigger and harsher with the seconds. When it passed him the stretch of road was completely dark. Then it was quiet. Not even summertime bugs were calling out from the muck, but a sad little wind pushed roadside litter in the ditch.

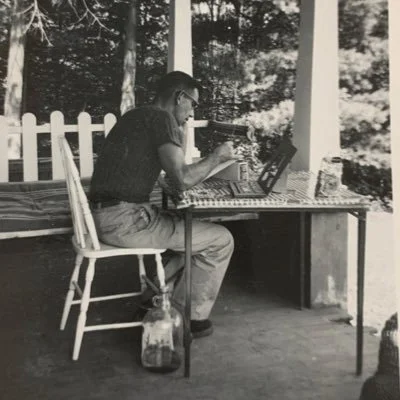

Photo of Chuck Strange

BIO: Chuck Strange is a rabbit farmer from the Northeast who clocks into the Short Fiction Factory Monday thru Friday. On Twitter: @Normal_Chuck. Find him at easterngray.substack.com.